Kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen) is an important Easter hymn in the Georgian Orthodox tradition.

It is sung when the priest knocks on the doors of the church, symbolizing entrance to the tomb of Christ, just before entering the sanctuary space to commence the all-night liturgy service.

Then it is repeated in groups of three throughout the All-Night vigil service (4-7 hours). It is also sung in every service after Easter until Pentecost.

The chant survives in many musical variants, as chanters in each village and region perfected their individual style. Take a look at the following video playlists to get a sense of the diversity of the music!

I've written up a number of transcriptions and posted them here for download for performance purposes only! Please credit your source. 🙂

Paschal Greetings and Vocabulary:

| Kriste aghdga! | Christ is Risen! |

| Cheshmaritad aghdga! | Indeed He is Risen! |

| Dideba upals! | Glorify Him! |

| Upalo shegvitsqalen | Lord have mercy |

| Aghdgoma | Pascha |

Notation:

This chant book includes six musical variants of the paschal troparion, kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen).

Audio: kriste aghdga (recommended)

Aghsavali Ensemble (many variants)

Sakhioba Ensemble (many variants)

Video: A playlist with 77+ Youtube recordings of kriste aghdga:

Text in Georgian:

Krist'e aghdga mk'vdretit

sik'vdilita sik'vdilisa

damtrgunveli da saplavebis shinata

tskhovrebis mimnich'ebeli.

Text in English:

Christ is risen from the dead,

trampling down death by death,

and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

Pronunciation:

If your international choir can get through the word mkvdretit, then you'll be fine. 🙂

Just kidding, the hardest to pronounce for many American speakers is the problematic 'r'. In all cases, this is a soft, flipped 'r' like in Spanish. Then there is a different sound in the throat ('gh'), that sounds like the way French pronounce 'r', as in the city name, Paris.

Here is a short guide to the most difficult consonants:

gh -- soft French ‘r’ in back of throat

mkv – these are ‘pick-up’ consonants to the sung syllable: -dre. The 'v' consonant ends up being pronounced like 'f'.

dre -- like drain, but flip the 'r' very softly, almost inaudibly (no American 'r'!!)

trgu – both the ‘t’ and the ‘r’ are produced by the tongue touching the back of the upper teeth, as in the Spanish flipped ‘r’ and adding the normal hard ‘g’ sound, and the 'oo' vowel. This should not be pronounced ‘ch’ as in ‘true.’

ts -- as in cats

kh -- also written as ‘x’ in phonetic alphabet, a gutteral sound that should not be over sung. If all else fails, skip it!

Kriste aghdga (Svanetian variants)

Video: 30+ performances of the popular variant from Svaneti

Kriste aghdga (Svaneti variant)

The most popular variant of the Paschal troparion in Georgia is quite possibly the variant from Svaneti - a highland region in northwest Georgia that preserves ancient layers of Kartvelian culture (archaic forms of language, folk music, agrarian tradition, Christian arts, etc.)

As can be seen in the playlist of performances of this variant, it often begins with a solo sung by the middle voice. The top voice joins with the melody, while the bass harmonizes with typical Svanetian chord types (fifth and seventh intervals below the melody).

Choirs often perform this chant with brusque, husky or burly sounding vocal affects, a nod towards Svan folk musical style. Performing this variant with this vocal style has somehow codified in popular imagination, such that even teenage girls (unnaturally and unnecessarily) try to mimic this style.

Characteristics of Traditional Georgian chant:

1) Traditional chant is almost always 3-voiced, not more not less.

2) Traditional chant is sung in "close harmony": the dissonances are integral to the desired sound. The tension-release in the music is symbolic of our prayers and supplications to God.

3) Traditional chants end in unison. Many Georgian chanters will confide that like the Trinity, the three voices of Georgian chant come together as One, and that is the reason that most chants end in unison.

4) Traditional chant is organized around fixed model melody fragments that are sung in the top voice. To lose the model melody is to lose the chant, as the harmony is based on the melody.

5) Traditional chant follows strict conventions of harmonization. The lower voices harmonize the model melodies according to local aesthetic taste, developed and vetted through centuries of oral tradition.

6) Traditional chant likewise follows strict conventions of ornamentation. By expanding the ornamentation with "foreign" flourishes, it loses the local character developed and vetted through centuries of oral tradition.

7) Traditional chant performance was a privilege, a guild. Master chanters trained for 5-6 years to attain proficiency in hundreds of model melodies, harmonization and ornamentation techniques, and the complex rubrics of the Orthodox rite. Thus, it is possible to imagine that upstart composers with a couple of years of Conservatory training, no matter how talented, were not immediately accepted members of the chanter's "guild."

Performance Tips:

There are a number of ways to perform this chant.

Georgian choirs tend to change their performance technique based on the variant. For example, the Svaneti variant is often sung in a very strong brusque voice, perhaps trying to emulate Svanetian folk singing. The Erkomaishvili and Patarava variants from the Guria region (Shemokmedi monastery style) are often sung by trios similar to the folksong trio genre popularized by these very singers in the early 20th century.

As a choir director, one has to make choices between trying to preserve some "authentic" performance practice, and being realistic about the capabilities of one's choir members. Calling something "authentic" is of course problematic because there was so much variation even within the known traditional-singing community in the early 20th century. That disclaimer aside, here are some suggestions.

Sounding Georgian:

- - One singer on the top voice

- - One singer on the middle voice

- - Optional number of singers on the lowest voice (good vocal balance typically demands 3-5 singers)

- - develop individual voices to have an narrow, cutting, bright timbre

- - develop a bass choral sound that supports the laser focus of the upper voices

- - the "sacred" feel of the sound is in the mental and physical approach to the texts, not in any acquired vocal affect

- - men, women, or children can sing, but it must be "close" harmony. Doubling at the octave is an imported musical feature.

- - timbre should be natural (tenors and sopranos in their mid-range, altos and basses in their mid-range). This is why most Georgian choirs, given the choice, elect to sing TTB, or SSA, rather than mixed gender choirs.

Kriste aghdga (West Georgian variants)

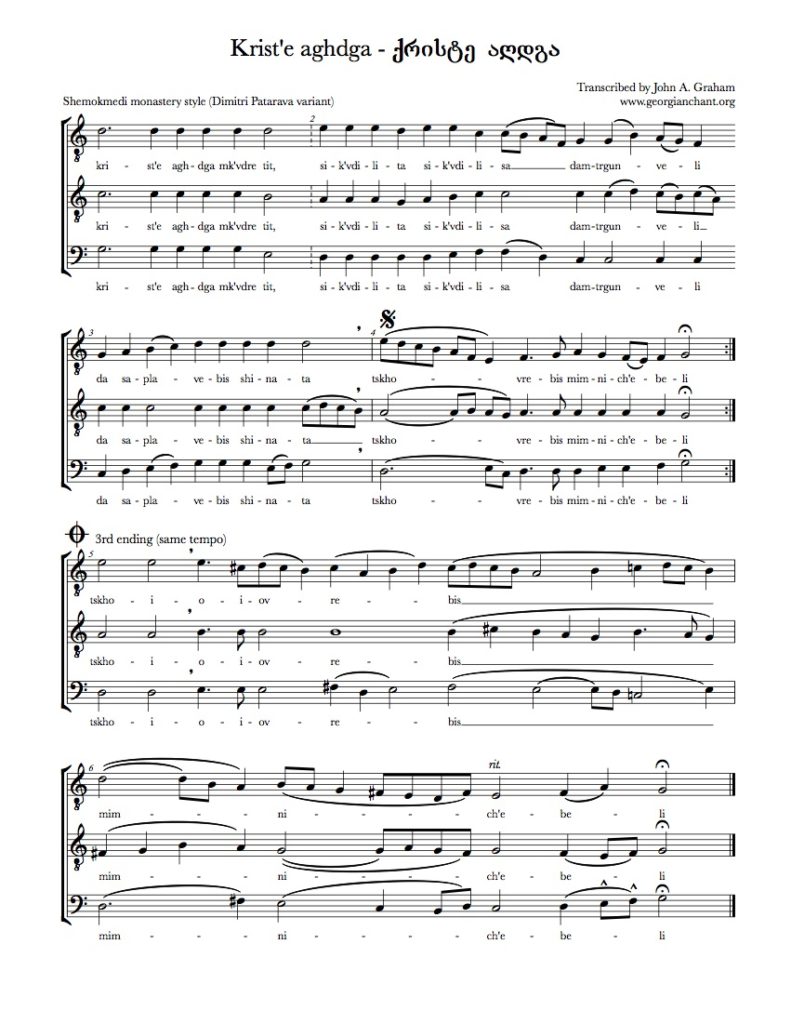

Video: performances of the Dimitri Patarava variant

Kriste aghdga (Patarava variant)

Dimitri Patarava (1886-1954) was one of the last "grand-masters" of Georgian chant, an inheritor of the unique oral tradition of liturgical chant passed down for generations at the Shemokmedi Monastery in West Georgia.

His variant of kriste aghdga was transcribed into European notation by his son Mamia Patarava sometime in the 1950s. It is similar to other variants from the Shemokmedi Monastery, but offers a unique take on how to harmonize the familiar melody. Note the first medial cadence on a seventh chord! This unusual cadence chord reveals itself as a brilliant segue to the second phrase, which launches with a 1-5-9 chord on the text sikvdilita....

At the third repeat of the chant, Patarava performs the words tskhovrebis mimnichebeli as an extended coda-like improvisation. The up-tempo interplay of the upper voices (two voice crossings!), combined with the simple but solid counterpart in the bass voice demonstrates the creativity and musical genius of the master chanters: they took a simple melody and molded it into extraordinary three-voiced improvisational polyphony.

Video: performances of the Erkomaishvili variant - West Georgia

Kriste aghdga (Erkomaishvili variant)

Artem Erkomaishvili (1887-1967) is regarded as the last master chanter of the oral tradition of Georgian liturgical chant. He admitted to knowing thousands of chants by heart, and left remarkable sources that continue to inspire chanters and scholars of Georgian chant. Among these are:

- 100+ cassette recordings of his voice singing all three voice-parts to complex chants, one after the other.

- a book full of texts with unique neume notation

- video of several folk songs and chants

- many transcriptions of his chants and folk songs

- important historical information, and performance practice information relayed through recorded interviews

In this variant of kriste aghdga, Erkomaishvili establishes a wide range by starting the bass voice at an octave below the melody. This allows both of the lower harmonizing voices to improvise with a range of flexibility, resulting in dramatic ascending and descending lines in the bass voice especially.

Harmonically, Erkomaishvili favored the 1-5-9 chord for all strong moments. This can be seen at the beginning of the second phrase on the word sik'vdilita, and the fourth phrase on the word tskhovrebis. Arguably, the 1-2-9 chord at the beginning of the third phrase on the word damtrgunveli is a variant of his favorite 1-5-9 chord.

Audio: Erkomaishvili variant of kriste aghdga

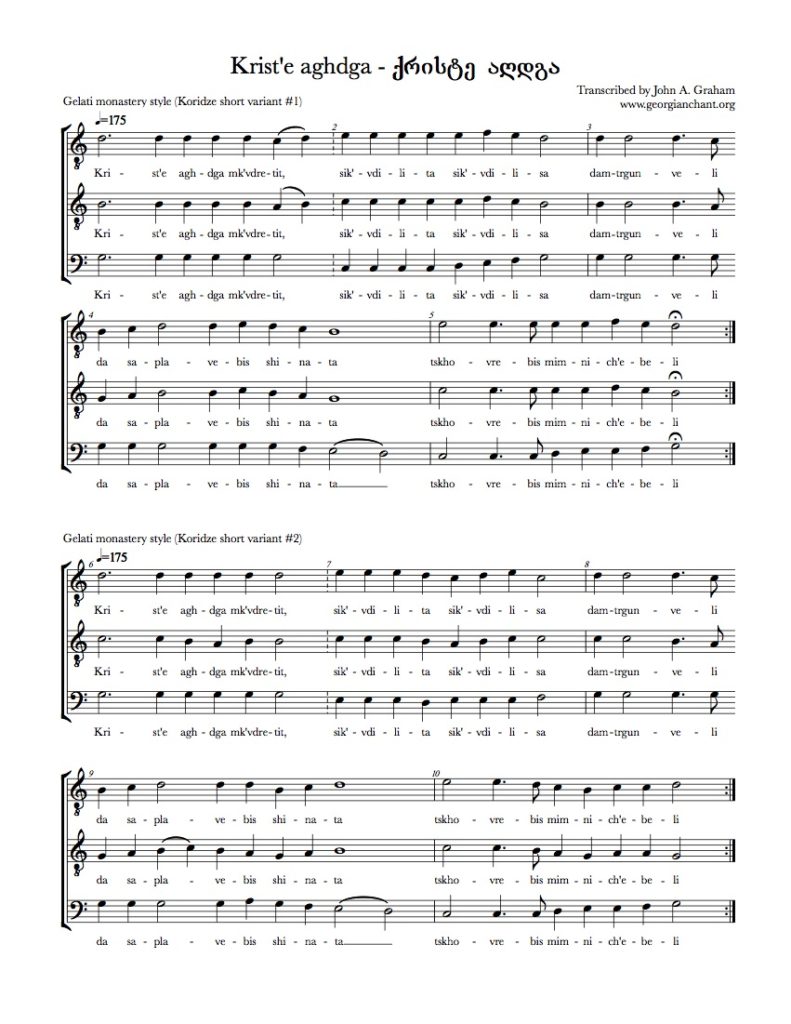

Video: "Kriste aghdga" - Koridze short variants - Gelati Monastery style (West Georgia):

Kriste aghdga (Koridze short variants - West Georgia)

Pilmon Koridze (1835-1911) was a trained opera singer who starred in Italy and St. Petersburg as a bass singer. Starting in 1883 he gave up his stage career and devoted himself to transcribing Georgian liturgical chant from the last master singers around the country. The 2000+ chants that he transcribed form the basis for our knowledge of Georgian chant today.

These two Kriste Aghdga variants were likely transcribed from singers in the Gelati Monastery area of West-Central Georgia in 1885-1886.

Video: Koridze long variant - Gelati Monastery style (West Georgia)

Kriste aghdga (Koridze long variant - West Georgia)

This variant has an extended coda for the final phrase, which is an optional ending for the third time through singing it.

In the original transcription, Koridze did not indicate any sharps or flats. I added three sharps in this transcription to avoid excessive tritone and half-step intervals, which are uncharacteristic intervals in Georgian traditional polyphony. In reality, the master singers had their own tuning system which can be heard on some old recordings.

This tuning system included neutral thirds, sixths, and sevenths. Therefore, if we consider E to be scale degree 1, G#, C#, and D should all be sung in a neutral position (in the cents system, Georgian intervals are about 160-170 cents apart, as opposed to the 100=half step or 200= whole step diatonic system Westerners are familiar with).

Video: The Benia Mikadze variant (West Georgia):

Kriste aghdga (Mikadze variant)

Benia Mikadze (1914-1997) left a treasure of Imeretian folk songs and chants.

He lived nearly his entire life in the small village of Khiblari in the Lower Imereti region, and was the last of his generation of singers raised in the oral tradition of singing in the family. His variants are entirely local, and were picked up from his parents, grandparents, and their friends.

His songs and chants have been popularized by the influential choir director, Malkhaz Erkvanidze (Anchiskhati Ensemble, Sakhioba Ensemble, international workshop leader).

Video: The variant from Lechkhumi (West Georgia):

Kriste aghdga (Lechkhmuri regional variant)

This variant of Kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen) is from the mountain region of Lechkhumi. This region is situated along one tributary system of the Rioni River, nestled between the mountainous valleys of Upper Imereti, Racha, and Svaneti.

Musically, this variant closely resembles that sung by Benia Mikadze (1914-1997), but also the Svanetian and Rachan variants.

It is not frequently sung, but I did find a video performance by the Tao Choir (see video above), and made a transcription of that performance (see notation to the right).

Video: The variant from Racha (West Georgia):

Kriste aghdga (Rachan regional variants)

There are several variants of Kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen) from the highland region of Racha, which neighbors the regions of Upper Imereti, Lechkhumi, and Svaneti.

At least one variant is a round-dance. This would have been sung at the feasts following the Paschal vigil, with extra para-liturgical praise texts added to it.

I will try to add more information here as I learn it, as well as notation!

Audio (historical): Rachan round-dance variant of kriste aghdga

Rachan round-dance variant, Rostom Gogoladze Choir

Kriste aghdga (Rachan regional variant)

This amazing recording was uncovered among historical wax cylinders from 1916. Georgian soldiers in Berlin were recorded singing several songs, and one of them was a Rachan variant of Kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen). Amazing to have these voices still audible to us today.

Audio (historical): Rachan variant of kriste aghdga

Rachan variant, recorded in a WWI German prisoner-of-war camp between 1916-1918.

Kriste aghdga (Megrelian regional variant)

This variant of Kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen), from the Samegrelo region of West Georgia, is relatively unknown. When I learn more about who recorded it or transcribed it, I will try to add more information here. In one of the videos here, Levan Veshapidze has usefully provided notation.

Video: The variant from Samegrelo (West Georgia):

Kriste aghdga (East Georgian variants)

Video: Karbelashvili #2 variant - Svetitskhoveli Monastery style (East Georgia)

Kriste aghdga (Karbelashvili variants - East Georgia)

The Karbelashvili family preserved the oral tradition of liturgical chant in Georgia throughout the 19th century.

During this period, the Georgian Church was under the supervision (some would call it suppression) of the Russian Orthodox Church and its appointed Exarch from St. Petersburg. Some exarchs favored Georgian Orthodox culture, frescoes, singing... but the vast majority of them did not. The seminaries were conducted in Russian, and Russian 4-part harmony chant was taught and disseminated via the seminaries. As a result, the knowledge of Georgian three-voiced traditional chant went into decline as the transmission of this music in Church institutions was usurped by Russian Orthodox cultural norms. For more on this topic, see the dissertation, "The Transcription and Transmission of Georgian Liturgical Chant" (John A. Graham, Princeton, 2015).

Petre Karbela-Khmaladze (1754-1848) studied East Georgian chant in the 1700s in the Davit Gareji Monastery and the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral. His son Grigol (1812-1880) was a professional chanter and taught at the Bodbe Monastery in 1860-1861, and later at the Tbilisi Seminary for a brief period. Grigol's five sons were the last generation of highly-knowledgeable master chanters. Vasil (1858-1936), in particular, was instrumental in preserving this important school of Georgian traditional chant. After learning European notation, he personally transcribed some 500 ornamental chants. His brother Poliekvtos transcribed simple chant variants. Other composers such as Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov also transcribed chants from the Karbelashvili brothers in the 1880s.

The melodies of the Vasil Karbelashvili variants are the same as the West Georgian variants, but the lower harmonizing voices are quite different. The middle voice displays the kind of ornamentation favored in East Georgia: a flowing line that passes between one chord and the next.

There are at least two variants (if not more). Here I provide notation for "Variant #1", and "Variant #2."

Performance tips:

- The tempo should be on the faster side, between 100-120 beats per minute (quarter note), but not so fast that the middle voice passing tones seem aggressive or forced.

- Karbelashvili chant should have a feeling like a large slow river, moving surely, steadfastedly, with pride, majesty, and inexorable inevitability towards the cadence.

- Individual chords are not prioritized, but rather the entire motion of the phrase, sung in one breath.

Kriste aghdga (20th c. composed variants)

Video: The Paliashvili 6-voice arrangement from 1909 (East Georgia):

Kriste aghdga (Zakaria Paliashvili arrangement - East Georgia)

Zakaria Paliashvili (1871-1933) is an important Georgian composer. He is buried outside the Tbilisi Opera House, which was posthumously named after him in 1937. Paliashvili is the composer of two operas (Abselom da Eteri 1919; Daisi 1921) that are considered the foundations of Georgian opera.

He studied with Sergei Taneyev at the Moscow Conservatory in 1903-1904, and was deeply influenced by the Smolensky-led movement to compose new sacred music for large choir based on old Russian znamenny chant melodies. Upon his return to Georgia in 1904, Paliashvili began his own arrangements of traditional melodies, using the recent publications of Karbelashvili East-Georgian chant. His arrangements were published as a "Liturgia" in 1909, and included a kriste aghdga arranged for six voiced large chorus (SSATTB).

Unfortunately, this piece was rarely performed, as world events such as the World War and communist governments did not provide a conducive environment for the performance of sacred music. It has not been recorded by a Georgian choir.

Very recently, however, the Paliashvili "Liturgia" has received international recognition. The video above is a performance by the Capitol Hill Chorale in Washington DC, who released the first compact disk recording of the entire Liturgia in the Georgian language, as well as the redacted score. For more information, see this article written by John A. Graham and Parker Jayne.

Video: A popular 20th century composed variant (East Georgia):

Kriste aghdga (Composed variant - East Georgia)

In 1978, the new choir director of the Sioni Cathedral in Tbilisi (he later became Priest Pavle Berishvili) undertook to write a whole new set of music for the Vespers-Matins-Divine Liturgy cycle. At that time, nothing was known of the lost Georgian traditional chant, as the oral tradition was lost and the manuscripts that represented that tradition were sealed in State Archives.

This version of kriste aghdga, and many other popular chants, apparently were written by Father Pavle. (It was quite difficult to discover this information, thank you to Levan Bitarovi for the link to this article about Priest Pavle Berishvili in Georgian).

I don't know if there are original transcriptions anywhere, I've certainly never seen them published. But I've transcribed some of the performances of this composed variant and attach them here (they all vary slightly, meaning that this chant has gone back into oral tradition):

Compare Performances:

Video Playlist: Kriste aghdga

(Georgian choirs)

Video Playlist: Kriste aghdga

(International choirs)

Video Playlist: Kriste aghdga

(Womens-Mixed choirs)

Video Playlist: Kriste aghdga

(Men's choirs)

We welcome your questions and comments!

Kriste Aghdga [Christ is Risen] in English - John Graham Tours

[…] Main page […]

Radek

Thanks very much, this is more than I hoped for, searching for Qriste Aghdga. I wonder, regarding the “Mzdlevari” version of the “Compare performances” section, can you match it to any of the traditional version?

Dmitrii

Thaks for your job! God blessed you!

Дмитрий

Thaks for your job! God blessed you!

Georgian Easter chant - Christ is Risen - Georgian Chant

[…] Kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen) – Georgian Easter chants […]

Igor

John,

What about the second part following the Kriste aghdga (Svanetian variant) sung quietly by МДЗЛЕВАРИ in https://youtu.be/cP68IqBiIl4?t=1m28s ? What is it called? Do you happen to know its lyrics and score?

JohnGrahamTours

At 1:34, the choir switches to singing “aghdgomasa shensa” (To your Resurrection), another Easter chant. This is sung at the end of the Vespers service as the icons are paraded around the exterior of the church, and just before the entrance back into the sanctuary when we first discover that Christ is resurrected, and sing for the first time “Christ is Risen!” The variant that this choir sings is from Guria, and was transcribed from master chanter Artem Erkomaishvili in the 1960s by his grandson Anzor Erkomaishvili. The performance style, singing quietly bel canto, was popularized by the Rustavi Ensemble (dir. by Anzor Erkomaishvili). In reality, singing this chant outside while processing around the exterior of the church, should be sung full throated just like the “Christ is Risen” before it, or perhaps even more so. Thanks for your question.

Nick Emmett

Thank you John for having created such a comprehensive and enjoyable resource for those of us who love Georgian songs and love singing them.I’m in the early stages of building a Georgian music choir in the UK and it’s really helpful to have your notes on voice balance and style of singing.

I look forward to visiting Georgia again and joining one of your tours soon.

Best wishes,

Nick

John

Thank you Nick, I look forward to hearing your music!

Toba Goddard

What marvelous samples of songs with bonuses of correct pronunciation, history and variants of song along with transcriptions!!! I have traveled to Georgia, but I suspect my uneducated being only scratched the surface of this wondrous country! I look forward to going on one of John’s tours…I’m thinking 2020.

Gmadlobt John.

JohnGrahamTours

Thank you Toba. Let me know if you try to sing any of these variants!

mira

well done! thank you very much for your work. didi madloba 🙂

JohnGrahamTours

My pleasure Mira, I’m glad that you found it useful!